History, Food and Poetry in Paterson, NJ

Anthony

December 28, 2016

Paterson, the bus driver poet played by Adam Driver in Jim Jarmusch’s new movie of the same name, finds inspiration in the routines of his blue-collar community, composing verse while sitting on a bench facing the Great Falls. Something about Paterson, New Jersey, and its waterfall, has attracted dreamers and storytellers for centuries.

Great Falls National Historical Park is tapping into the creativity sparked by its location, using stories about food to connect Paterson’s history to the people who live there.

Paterson, NJ

Paterson’s history is a very American story of abundant natural resources, immigrant labor and sacrifice, economic booms and busts, and diverse communities living and struggling together.

Paterson’s history is a very American story of abundant natural resources, immigrant labor and sacrifice, economic booms and busts, and diverse communities living and struggling together.

The wide, rocky bend where the Passaic River crashes seventy-seven feet over basalt cliffs, spoke to Alexander Hamilton, who chose the location as the site for America’s first planned industrial city in 1792. Our country’s first Treasury Secretary wanted to ease the young nation’s reliance on manufactured goods imported from England. An immigrant himself, Hamilton envisioned a hub of industry and innovation harnessing the power of the great Falls, driven by immigrants’ “diversity of talents.”

Hamilton’s original plan fizzled after a single textile mill, a financial panic, and some embezzlement by the manufacturing society’s directors, but Paterson survived. Thanks to an ingenious “raceway” system of canals along the Passaic, and a steady stream of immigrant labor, Paterson became an early industrial powerhouse of the United States. For more than a century from the early 1800s, Paterson was a major manufacturing center, its factories and workers churning out textiles, firearms, locomotives and the world class silk that gave the town its nickname. Generations of immigrants – from England, Ireland, Germany, Italy, Eastern Europe and the Middle East – toiled in the Silk City’s factories and fuelled Paterson’s impressive population growth. In 1900, Paterson was the fastest growing city on the East Coast. By 1910, Paterson had 300 factories employing more than 18,000 workers.

Hamilton’s original plan fizzled after a single textile mill, a financial panic, and some embezzlement by the manufacturing society’s directors, but Paterson survived. Thanks to an ingenious “raceway” system of canals along the Passaic, and a steady stream of immigrant labor, Paterson became an early industrial powerhouse of the United States. For more than a century from the early 1800s, Paterson was a major manufacturing center, its factories and workers churning out textiles, firearms, locomotives and the world class silk that gave the town its nickname. Generations of immigrants – from England, Ireland, Germany, Italy, Eastern Europe and the Middle East – toiled in the Silk City’s factories and fuelled Paterson’s impressive population growth. In 1900, Paterson was the fastest growing city on the East Coast. By 1910, Paterson had 300 factories employing more than 18,000 workers.

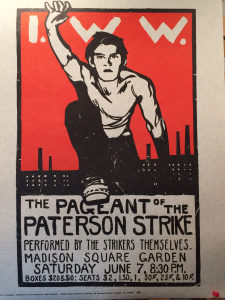

Paterson’s economic success had a dark side, including squalid living conditions for the City’s poor and the widespread exploitation of working adults, and many children, in its factories. Paterson’s workers often protested abusive working conditions, such as during the six-month-long Their struggles played a key role launching the American trade union movement, which ultimately led to laws banning child labor and securing the eight-hour workday.silk strike of 1913.

Paterson’s fortunes rose again in the first half of the Twentieth Century, with a growing middle class fuelled by descendants of the City’s first-generation immigrants. As Paterson’s factories closed and the post-World War II economic boom ended, however, the City’s economic base shifted away from manufacturing and entered a decades-long decline. The City has endured high rates of unemployment and poverty since the 1970s. Despite the struggling economy, the size of Paterson’s population has remained stable, unlike many other formerly industrial cities, largely due to foreign immigration replacing migration from Paterson to the surrounding suburbs.

Two and a quarter centuries after its founding, Paterson is the most densely populated city in the most densely populated state, and the third largest city in New Jersey with some 148,000 residents.

True to its history, Paterson remains a city of immigrants. A third of Paterson’s current residents were born outside the United States – with large numbers from the Dominican Republic, Peru, Mexico, Jamaica, Bangladesh and the Middle East. The city is home to a Peruvian Consulate and one of the largest Arab-American communities in the U.S. Patersonians today sustain the local economy, not as factory workers, but as service providers and small business owners.

Poetry

The rise and fall of the “American Dream” in Paterson is the stuff of poetry. William Carlos Williams, in his epic poem, “Paterson” (1946-58), reimagines the Great Falls as the “image of the City as a man . . . peopling the place with his thoughts”:

“The past above, the future below

and the present pouring down: the roar,

the roar of the present, a speech –

is, of necessity, my sole concern.”

– William Carlos Williams, “Paterson”

Paterson also appears in the poetry of Allen Ginsburg, whose father taught English at Paterson’s Central High School for 40 years. In the movie Paterson, look for the William Carlos Williams volume on the bus driver’s basement table.

Great Falls National Park

Paterson’s Great Falls became a U.S. National Historic Park in 2011. Since then, the National Parks Service has worked to attract new visitors. At least 180,000 people visited the Park last year, according to Ilyse Goldman, the Park Ranger supervising resource education at the Great Falls. Visitors include local residents, New Jersey school groups, National Park fans checking off the Great Falls (the second highest waterfall east of the Mississippi river, after Niagara Falls), and casual visitors drawn to visit the Falls from outside of Paterson. Because there is no fixed entrance to this urban Historic Park, the total is an estimate, but the number of visitors has “grown significantly” in the past few years. One source of growth is undoubtedly the renewed interest in all things Hamilton since that show took Broadway by storm.

Paterson’s Great Falls became a U.S. National Historic Park in 2011. Since then, the National Parks Service has worked to attract new visitors. At least 180,000 people visited the Park last year, according to Ilyse Goldman, the Park Ranger supervising resource education at the Great Falls. Visitors include local residents, New Jersey school groups, National Park fans checking off the Great Falls (the second highest waterfall east of the Mississippi river, after Niagara Falls), and casual visitors drawn to visit the Falls from outside of Paterson. Because there is no fixed entrance to this urban Historic Park, the total is an estimate, but the number of visitors has “grown significantly” in the past few years. One source of growth is undoubtedly the renewed interest in all things Hamilton since that show took Broadway by storm.

“The Great Falls are a mind-blowing natural wonder in the middle of a city.”

– Robin Gold, Hamilton Partnership

Continuing to attract new visitors is no easy task. The Park faces a number of challenges as one of the nation’s newest and smallest urban National Parks. According to Robin Gold, Program Director of the Hamilton Partnership for Paterson, the Great Falls is unique among National Historic Parks with a “mind-blowing natural wonder in the middle of a city,” yet many local residents, even in Paterson, “still don’t know that the Falls are now a National Park.”

While there are plans in the works to develop the Park’s infrastructure in the coming years, right now there’s not much more to the National Park than the naturally impressive Falls themselves. A Welcome Center provides Park information, serves as the starting point for ranger-led guided tours, and houses a small gift shop. There are no other official Park buildings to visit. The City of Paterson owns the parkland surrounding the Falls in the Historic District, as well as the Paterson Museum in one of the original factory buildings, which houses local archaeology, history, and mineralogy collections. You can easily park in the free Park lot, take in the impressive view of the Falls, and walk the short circuit across the footbridge over the river gorge in less than an hour.

While there are plans in the works to develop the Park’s infrastructure in the coming years, right now there’s not much more to the National Park than the naturally impressive Falls themselves. A Welcome Center provides Park information, serves as the starting point for ranger-led guided tours, and houses a small gift shop. There are no other official Park buildings to visit. The City of Paterson owns the parkland surrounding the Falls in the Historic District, as well as the Paterson Museum in one of the original factory buildings, which houses local archaeology, history, and mineralogy collections. You can easily park in the free Park lot, take in the impressive view of the Falls, and walk the short circuit across the footbridge over the river gorge in less than an hour.

The Great Falls National Park and the commercial districts of Paterson are largely isolated from one another. Perched above downtown Paterson, nothing in the landscape encourages visitors to walk down the hill. Visitors from outside of Paterson typically visit the Falls, snap a picture of the bronze Alexander Hamilton statue, and leave. Paterson residents might climb the hill to eat lunch at the picnic table next to the Hamilton statue, or pass by the Falls on their way between downtown and the Totowa section neighborhood.

How do you get more local residents to visit, while encouraging Park visitors to explore New Jersey’s most densely populated city?

How do you get more local residents to visit, while encouraging Park visitors to explore New Jersey’s most densely populated city? The answer: food stories.

The Park Service has emphasized developing the Park’s interpretative resources, investing in educational programs and social media outreach. The Park Service’s Goldman, for example, is partnering with a local middle school to design an innovative three-year curriculum around immigrant experiences throughout Paterson’s history. Students visit the Park and other area educational sites to learn about immigrant contributions to American history.

The Park Service has emphasized developing the Park’s interpretative resources, investing in educational programs and social media outreach. The Park Service’s Goldman, for example, is partnering with a local middle school to design an innovative three-year curriculum around immigrant experiences throughout Paterson’s history. Students visit the Park and other area educational sites to learn about immigrant contributions to American history.

Through her work on the school curriculum, Goldman has learned that stories about food are a powerful way to teach immigration history. “Everyone has a story about their grandmother’s favorite dish,” Goldman points out.

“Everyone has a story about their grandmother’s favorite dish.”

– Ilyse Goldman, National Park Service

Food

Food emerged as a powerful storytelling tool in last year’s National Parks Now competition, sponsored by the New York City-based non-profit Van Alen Institute. The design competition sought proposals to “attract new audiences, develop unconventional partnerships, make historic narratives relevant to new generations, and encourage immersion into natural landscapes” for four lesser known northeastern National Parks: Sagamore Hill (Oyster Bay, NY), Steamtown National Historic Site (Scranton, PA), Weir Farm (Wilton, CT), and Paterson’s Great Falls.

Food emerged as a powerful storytelling tool in last year’s National Parks Now competition, sponsored by the New York City-based non-profit Van Alen Institute. The design competition sought proposals to “attract new audiences, develop unconventional partnerships, make historic narratives relevant to new generations, and encourage immersion into natural landscapes” for four lesser known northeastern National Parks: Sagamore Hill (Oyster Bay, NY), Steamtown National Historic Site (Scranton, PA), Weir Farm (Wilton, CT), and Paterson’s Great Falls.

Team Paterson, a multidisciplinary group of designers, historians and other experts, tackled the problem of attracting visitors to the Great Falls by thinking about ways to make connections between the Park and the largely immigrant community surrounding it. Immigration and industry were obvious themes, but how could the Park make connections between the past and present? How could they tell the story of the Great Falls in a way that is meaningful to Paterson’s current population?

Team Paterson, a multidisciplinary group of designers, historians and other experts, tackled the problem of attracting visitors to the Great Falls by thinking about ways to make connections between the Park and the largely immigrant community surrounding it. Immigration and industry were obvious themes, but how could the Park make connections between the past and present? How could they tell the story of the Great Falls in a way that is meaningful to Paterson’s current population?

When the group met in Paterson to consult with staff from the Park and the Hamilton Partnership, they often brainstormed over lunch. Team Paterson tried a different local restaurant each visit, sampling Peruvian ceviche, Argentinian empanadas, Turkish lahmajun, and Lebanese kanafeh along the way.

Food quickly emerged as a compelling and relevant way to connect the past and present, the community and Park visitors. “We realized that food is a common pathway,” says urban historian Mariana Mogilevich.

Food is at the center of Paterson’s cultural landscape.

Food is at the center of Paterson’s cultural landscape.

The narrative of the Great Falls in American history begins with a meal. In the midst of the Revolutionary War, George Washington, his aide Alexander Hamilton, and the French general Lafayette picnicked on the riverbank across from the Great Falls. On July 10, 1778, they ate a “’modest repast’ of cold ham, tongue and biscuits,” according to Hamilton’s biographer. The memory of that meal and its location led Hamilton to found Paterson at the Great Falls.

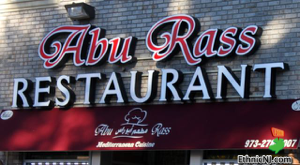

Today in Paterson, thanks to its diverse foreign-born population, you’ll find one of the widest arrays of global cuisine in New Jersey. Paterson neighborhoods include enclaves known for their ethnic food: “Little Lima” on Market Street for Peruvian; “Little Italy” around Cianci Street for Italian; and “Little Istanbul,” “Little Ramallah” or “Little Damascus,” depending on who’s talking, along Main Street in South Paterson for Middle Eastern fare.  Among the standout family-owned local restaurants are Patsy’s Tavern (Italian), La Tia Delia (Peruvian), Stone’s Original Jerk Chicken (Jamaican), Taskin Bakery (Turkish), Al Safa (Syrian) and Nablus Pastry (Palenstinian). And right next to the Great Falls is Libby’s Lunch, home of the iconic “Texas Weiner” style New Jersey hot dog.

Among the standout family-owned local restaurants are Patsy’s Tavern (Italian), La Tia Delia (Peruvian), Stone’s Original Jerk Chicken (Jamaican), Taskin Bakery (Turkish), Al Safa (Syrian) and Nablus Pastry (Palenstinian). And right next to the Great Falls is Libby’s Lunch, home of the iconic “Texas Weiner” style New Jersey hot dog.

By reinterpreting Paterson’s history through a food lens, Team Paterson realized they could make connections between the National Park and the City, and between the past and the present. Food became the storytelling thread connecting the history of the Great Falls to contemporary life in Paterson. “Food and eating is connected to living, breathing history,” notes Mogilevich.

“Food and eating is connected to living, breathing history.”

– Mariana Mogilevich, Team Paterson

Great Falls, Great Food, Great Stories

Team Paterson’s project proposal – “Great Falls, Great Food, Great Stories” – envisioned partnerships with local restaurants; food-related programming to bring the Park into the City, and the community into the Park; and new interpretive materials to tell the stories of Patersonians, past and present. Their project won the National Parks Now competition.

For the pilot phase of the project last year, Team Paterson developed eye-catching way-finding posters – like “← Great Falls / Great Ceviche → ” – for display in the windows of three Peruvian restaurants adjacent to the Park on Market Street. The pilot culminated with project and Park staff visiting the local restaurants.

For the pilot phase of the project last year, Team Paterson developed eye-catching way-finding posters – like “← Great Falls / Great Ceviche → ” – for display in the windows of three Peruvian restaurants adjacent to the Park on Market Street. The pilot culminated with project and Park staff visiting the local restaurants.

With additional funding from the NJ Council for the Humanities, the second phase of the project highlighted the proximity of the Park to popular local restaurants in two Paterson neighborhoods, on Market Street in downtown Paterson, and a 10-minute drive from the Park along Main Street in South Paterson. Participating restaurants were listed in a new map for Park visitors. The fifteen restaurants are a cross-section of Paterson’s diverse food options, including Costa Marina, Dulcemente Peruano, and Panchito’s (Peruvian) on Market Street, and Al Basha (Lebanese), Nouri’s (Syrian), Toros (Turkish) and Abu Rass (Palestinian) on Main Street. To introduce restaurant patrons to the Park, each restaurant was provided placemats branded with the project slogan “Great Falls, Great Food, Great Stories”.

Coinciding with the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service in August of this year, the “Savor Paterson” food festival – featuring local restaurants serving a diverse array of Paterson’s global cuisine – brought hundreds of people, largely families, to the Great Falls on a summer evening.

At the center of the project is an effort to tell Paterson’s story in creative ways.  A new brochure available at the Park’s Visitor’s Center makes the connections between history, food, community and immigration:

A new brochure available at the Park’s Visitor’s Center makes the connections between history, food, community and immigration:

“People on Paterson have always worked hard to put food on the table – and they have always enjoyed the landscape of the Great Falls. They have strived to preserve their heritage while adopting new cultures and customs. Their story is the same today. The businesses, foods, and languages may have changed, but the dream is the same.”

– “Great Falls, Great Food, Great Stories” brochure

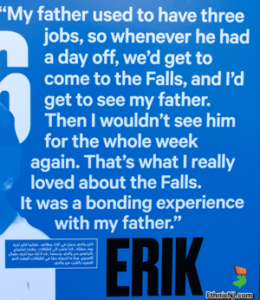

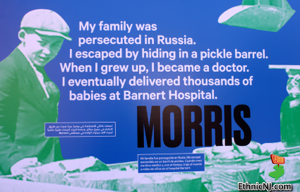

This fall, nine brightly colored “storyfronts” were strategically displayed around the City. Each large poster, illustrated with archival photos and historical drawings, recounts one aspect the City’s history with quotes from actual Paterson residents of different eras, from 1602 through 2016. The quotes demonstrate how different generations of Patersonians have had similar experiences, sprinkled with food-related details.

The “Different Cultures Meet in Paterson” storyboard, for example, an EthnicNJ favorite, features remarkably consistent testimony of diverse communities living together, and learning from one another in Paterson, for centuries:

“We brought fruits and vegetables from the Netherlands, but the land was different here. The Lenape introduced us to corn and squash and showed us how to grow them. . . .” – Gerrit, 1690

“My family is Irish but I had Italian friends, Jewish friends. One time I went to visit my Italian friends and they poured me a big glass of wine. I was only sixteen – I wasn’t used to it! They said: We do this at every meal!” – Mary, 1886

“An Irish patrolman came in to our pastry shop and he had never has these kinds of sweets before. He looked at the Kanafeh and said ‘Give me a piece of that carrot cake!’ It’s just a question of trying things. . . .” – Abdullah, 1998

“Our next door neighbor was from El Salvador, and we would eat her pupusas all the time. Before she moved away, she came over and taught me and my mother how we could make them ourselves.” – Yesi, 2000

Other storyboards quote Patersonians talking about immigration, family, work, food production and visiting the Falls. All text is translated in three languages: English, Spanish and Arabic.

Other storyboards quote Patersonians talking about immigration, family, work, food production and visiting the Falls. All text is translated in three languages: English, Spanish and Arabic.

The storyfronts around Paterson were temporary, but the brochure is still available at the Park Welcome Center. Ideally, the project can help to establish long-term partnerships between the Park, local restaurants and Paterson’s residents. The Hamilton Partnership’s Robin Gold notes that the project has already created new relationships between local restaurants and the Park. Participating restaurants closest to the Park, for example, report gaining some new customers as a result.

“Who lives, Who dies, Who tells your story?”

– Lin-Manuel Miranda

Great Falls, Great Food, Great Stories could become of model for the National Park Service to engage new audiences in creative ways. The project blurs the boundaries of the Park and remixes history in a way that engages people. What the musical Hamilton accomplishes using the language of hip-hop to connect new audiences to American history, the Great Falls National Park is doing on a smaller scale: using food as a common language to connect immigrant New Jersey’s present to the Falls, the Park and Paterson’s history.

Great Falls, Great Food, Great Stories could become of model for the National Park Service to engage new audiences in creative ways. The project blurs the boundaries of the Park and remixes history in a way that engages people. What the musical Hamilton accomplishes using the language of hip-hop to connect new audiences to American history, the Great Falls National Park is doing on a smaller scale: using food as a common language to connect immigrant New Jersey’s present to the Falls, the Park and Paterson’s history.

I imagine Alexander Hamilton, William Carlos Williams, and Adam Driver’s Paterson would approve.

by Anthony Ewing

BBQ

BBQ Brazilian

Brazilian British

British Chinese

Chinese Costa Rican

Costa Rican Cuban

Cuban Deli (Jewish)

Deli (Jewish) Diner

Diner Ethiopian

Ethiopian Filipino

Filipino German

German Indian

Indian Irish

Irish Italian

Italian Jamaican

Jamaican Japanese

Japanese Korean

Korean Mexican

Mexican Middle Eastern

Middle Eastern Persian

Persian Peruvian

Peruvian Portuguese

Portuguese Taiwanese

Taiwanese Thai

Thai Trinidadian

Trinidadian Turkish

Turkish Vietnamese

Vietnamese