The Many Flavors of Desi Jersey

Anthony

May 1, 2013

Indian food is fairly easy to find across New Jersey these days. Most Indian restaurants serve familiar dishes, the curries, kebabs and flatbreads originating in North Indian regions, like the Punjab. It takes a little more work, however, to find India’s other regional specialties, the South Indian dosas, Gujarati dhoklas and Indo-Chinese chili chicken Hakka style sought out by Indian-Americans.

While Jersey City’s “Little India” (Newark Avenue), Parsippany (along Route 46), and Cherry Hill (outside Camden) boast clusters of eateries featuring the rich variety of South Asian cuisine, it is the Route 27/Route 1 corridor from Woodbridge to South Brunswick that is home to some of the best and most diverse Indian food New Jersey’s South Asian community has to offer.

The two-mile stretch of Oak Tree Road from Iselin to Edison is the place in Jersey to sample Indian food that goes beyond, way beyond, the typical Indian dishes familiar to most Americans of non–South Asian ancestry. With over a hundred thousand Indian residents, suburban Middlesex County has the third-largest Asian Indian community in the United States; only Santa Clara, California, and Queens, New York, have larger Indian populations. South Asian, or “Desi,” immigrants have transformed this area in little more than a single generation. In the 1970s, the combination of Indian professionals living in Jersey City and Queens looking for suburban homes; strong public schools near high-tech employers; and commercial strips losing business to malls sparked the rapid growth of the Indian community centered around Oak Tree Road. Thanks to this concentration, “Oak Tree Road has a greater density and variety of Indian restaurants than any other Desi community in the country,” says Chitra Agrawal, an Indian-American food blogger and cooking teacher who grew up in New Jersey. “Relatives visiting from India know about Oak Tree Road and ask to eat there.”

Like the words “Mexican” or “Chinese,” “Indian” is the catchall American description of what is, in fact, many regional cuisines (and often the shared historical cuisines of India’s South Asian neighbors—Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka). North Indian and Punjabi cuisine might be most familiar—meat dishes cooked with intense spice mixes (masalas) or grilled in a tandoor oven; flatbreads (roti, paratha, naan); deep-fried fritters (pakoras) and hearty rice biryanis—but Indian cuisine ranges far and wide. India comprises 35 different states and territories, after all. Many Indians are vegetarians, a diet reflected in India’s regional cuisines. South Indian food, mostly vegetarian, features sambar (spicy lentil stew), dosas (rice-and-lentil crepes) and idli (steamed rice cakes). Gujarati dishes highlight vegetables, chutneys and sweets. Indo-Chinese restaurants blend Indian spices with Chinese specialties for an entirely unique cuisine. It can all be found along Oak Tree Road, straddling the parkway at Exit 131.

There are so many South Asian restaurants tucked into Oak Tree Road’s strip mall shopping plazas, it is difficult to know where to start. Agrawal, who visits often, starts on the eastern end in the Iselin section of Woodbridge. She recommends Jassi Sweets Center (12 Marconi Ave., at the corner of Oak Tree Road) for savory Punjabi snacks like papri chaat (crunchy chips, yogurt and sweet and spicy chutneys) and boondi raita (fried balls of chickpea flour in spiced yogurt). I tried the excellent samosa chaat (fried samosa chunks instead of chips) on a recent visit, but what drew my attention was the colorful dessert case filled with sweets, rivaling any well-stocked Italian bakery counter. While I ordered a few pieces of the homemade gulab jamun (milk dumplings soaked in rose-flavored sugar syrup) to go, proprietor Jaswant Singh offered everyone in the shop samples of sweet sesame-seed balls, warm and fresh out of the oven. Apparently, this dessert has no specific name, it’s just a sweet he created. The balls are delicious—crumbly, but held together with moist, melted raw sugar. I ordered a small box to go. Two other customers, sisters Amna and Rabia Hakim, insisted I not leave the shop without trying the freshly pressed sugarcane juice, which they consider the best on Oak Tree Road. At their suggestion, I ordered mine with a little added spice (masala). The result is a refreshing, not too sweet, cold drink with hints of ginger and spice, sort of a South Asian “Arnold Palmer” made with chai.

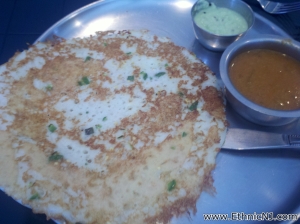

To experience the cuisine of South India as it might be served in Bangalore, go to the other end of Oak Tree Road to Edison’s all-vegetarian Swagath Gourmet (1700 Oak Tree Rd., westbound side). After taking a seat in the no-frills dining room, you are immediately served a small silver bowl of warm rasam, a sweet and spicy tamarind-flavored soup. The snack-sized dishes on the menu include vada (fritters), idli and the ubiquitous South Indian dosas (see sidebar). All are served with sambar, the spicy lentil stew, and at least one chutney, typically coconut and chili. Uttapam—thick rice-and-lentil pancakes —are also excellent for dipping. The intensely spiced rice dishes are also not to be missed at Swagath. Puliyogare, a rice specialty blended with tamarind and 14 herbs and spices is one of the most powerful plates of rice I’ve ever tasted. Every dish is served, literally, on a silver platter.

To sample the cuisine of Gujarat, a Western Indian state and the birthplace of Mahatma Gandhi, turn left and look for Jhupdi (1679 Oak Tree Rd., eastbound side), an Oak Tree Road standby for 13 years. From the comfortable wooden booths, one can gaze upon a tranquil rural village scene hand-painted along one wall. There is space for larger groups to feast while seated on the floor among plush pillows and woven floor coverings. For an appetizer, try the delicate khoman dhoklas, steamed chickpea flour cakes that taste like cornbread. The sweetness of the cakes contrasts nicely with the accompanying spicy chutneys. The samosa chaat here, a plate of fried samosa pieces covered with yogurt, chopped onions, green chutney and sweet chutney, blends sweet and spicy, soft and crunchy in a single, delectable spoonful.

Order a thali platter as a main course to sample many different Gujarati vegetable preparations, dips and breads. A thali here can be an adventure for the uninitiated and those with no working knowledge of the Gujarati language, like my wife and me. The Jhupdi Special thali we ordered arrived at the table on a steel platter with 10 different items in small metal containers, surrounding two millet-flour flatbreads (bajri rotla) for dipping. The waiter also placed a glass of buttermilk (chhas) on the table, which apparently comes with the platter. None of the vegetable mixtures was immediately identifiable for us, so we started tasting and guessing. The tastes included a sweet grain flavored with cardamom, a yellow spicy mashed potato, a split-lentil mixture (urad daal), a roasted eggplant salad (baigan bharatha), a squash-like vegetable mix, a yellow grain with green chilies, a chickpea-flour soup (kadhi), yogurt dip (raita), an obviously spicy red pepper we were afraid to touch, a crumbly sugary sweet, and a piece of what looked like a dark brown date. After we had sampled everything else, I encouraged my wife to try the date. She popped a small piece in her mouth and immediately chugged the buttermilk. Turns out, it wasn’t a fruit; it was a chili-garlic paste whose heat range hit somewhere near the top of the Scoville scale. Oops.

Spice addicts can easily become addicted to the chili garlic noodles at Ming (1655 Oak Tree Rd., eastbound side), an upscale Indo-Chinese restaurant in the same shopping center as the Big Cinemas Bollywood multiplex. Essentially lo mein noodles at Indian spice levels, the garlic and chili oil packs an irresistible wallop. I couldn’t stop eating these noodles (which I had with chicken and egg) as sweat beaded on my brow. Ming’s menu includes a wonderfully spicy-sour coriander soup, cauliflower Manchurian, and chili chicken Hakka style. “Hakka” refers to the Chinese ethnic group from Guangdong and Fujian provinces who settled the original Chinatowns of Calcutta, India. Chinese Hakka dishes met Indian masalas and Indo-Chinese cuisine was born.

Except for the upscale spots, like Ming and Moghul (right next door, emphasizing North Indian dishes and tandoori-grilled meats and breads), you’ll likely see few non-Indian customers at most Oak Tree Road restaurants. Language is generally not a problem for non-Hindi speakers, however, since most servers speak English. Menus may not translate everything, so don’t be shy about asking questions, especially if you are unsure about ingredients or spiciness.

One way to tell Jersey Indian restaurants apart, aside from vegetarian versus nonvegetarian menus and North Indian versus other regional cuisines, is by whether the default spice level of dishes has been reduced for (perceived) American tastes. Compare the food at Moghul and Ming’s sister restaurant, Mehndi, in Morristown, for example, with any Oak Tree Road Indian, and you will taste the difference. My spice-management strategy is to order a glass of lassi, the slightly salty, often fruit-flavored, yogurt drink with every Indian meal. Now, I know to add chhas and sugarcane juice to my drink roster. If anything sets your mouth on fire, a quick sip will douse the pain. It is a small price to pay to experience all the flavors of Desi Jersey on Oak Tree Road.

An original version of this post appeared as “Flavors of India” in Edible Jersey Magazine (Spring 2013).

BBQ

BBQ Brazilian

Brazilian British

British Chinese

Chinese Costa Rican

Costa Rican Cuban

Cuban Deli (Jewish)

Deli (Jewish) Diner

Diner Ethiopian

Ethiopian Filipino

Filipino German

German Indian

Indian Irish

Irish Italian

Italian Jamaican

Jamaican Japanese

Japanese Korean

Korean Mexican

Mexican Middle Eastern

Middle Eastern Persian

Persian Peruvian

Peruvian Portuguese

Portuguese Taiwanese

Taiwanese Thai

Thai Trinidadian

Trinidadian Turkish

Turkish Vietnamese

Vietnamese